di ANGELO RECALCATI

See the English translation at the bottom of the page.

Saggio pubblicato sul vol. X, 1997 di Achademia Leonardi Vinci. Journal of Leonardo Studies and Bibliography of Vinciana Edited by Carlo Pedretti.

Citato in: La Sainte Anne. L’ultime chef-d’oeuvre de Léonard de Vinci. Edition Louvre 2012. pp. 155, 431.

NEL 1482 Leonardo trentenne lasciò la natia Toscana e i suoi dolci colli verdeggianti di vigne e cipressi e giunse a Milano al centro della Valle Padana, piana umida e fertile dai lunghi filari di pioppi e gelsi immersi nella tipica atmosfera stagnante e nebbiosa. Vi giunse però in una delle non frequenti giornate in cui il vento del nord spazza la foschia, scoprendo all’orizzonte la gran cerchia delle Alpi. Quale maestosa visione! A un tempo promessa e stimolo di nuove prospettive, nuovi studi e nuove esperienze.

Questa suggestiva immagine poetica, suggerita da Gerolamo Calvi (1), ha ovviamente un significato esclusivamente simbolico, non essendoci alcun riferimento biografico che a essa si riferisca. Eppure negli oltre vent’anni che complessivamente trascorse a Milano, Leonardo ha certamente avuto la possibilità di familiarizzarsi con questa visione che, quantunque insolita, si verifica per parecchi giorni all’anno. Di ciò siamo ora certi: infatti uno dei tratti più significativi di questo panorama gli fu non solo familiare, ma lo interessò al punto da osservarlo e studiarlo a lungo e fissarlo in un disegno.

Leonardo fu il primo che alzò lo sguardo indagatore verso questa grandiosa corona di vette, e dopo lui dovranno trascorrere ancora quasi tre secoli prima che dalla pianura padana altri, avvertissero la ricchezza di conoscenze, esperienze e bellezza che potevano offrire le Alpi. (2)

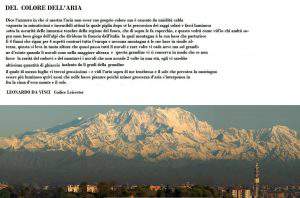

Il così evidente profilo di queste vette, a quel tempo inesplorate, ora rocciose ora innevate, fu certamente uno stimolo a intraprendere quelle „gite […] da fare nel mese di maggio‟ (3) che lo porteranno ad addentrarsi nell’area delle Prealpi e Alpi lombarde a cui si riferiscono le annotazioni nel Codice Atlantico (4). Nel Codice Leicester (5) abbiamo invece il resoconto di una sua escursione nella medio alta montagna, sulle pendici del „mon Boso‟, l’antica denominazione del M. Rosa (6). A differenza del Codice Atlantico, dove in qualche caso le annotazioni sono così impersonali da poterle considerare appunti da notizie avute da altri, qui Leonardo sottolinea in modo inequivocabile la sua esperienza diretta. Una esperienza che lo ha profondamente colpito: la testimonianza di un ambiente dalle caratteristiche così lontane da quelle del vivere quotidiano viene rafforzata da quell’epica frase „e questo vedrà, come vid’io, chi andrà sopra mon Boso, giogo dell’Alpi […]‟ quasi ad anticipare dubbi e incredulità del tutto legittimi, dal momento che l’esperienza dell’alta montagna cesserà di essere raro e singolare episodio per diventare patrimonio comune solo tre secoli dopo. In questa emozionante pagina del Codice Leicester intitolata „Del colore dell’aria‟ si incontrano e si fondono i suoi due interessi principali: la Pittura e la Scienza. Due interessi che in Leonardo crescono e si sviluppano in simbiosi per tendere ad una forma di conoscenza creativa totale, concezione che trova nel Libro di Pittura la sua compiuta formulazione(7).

ALLA VISIONE della montagna Leonardo dedica ampio spazio nel Libro di Pittura, sia nella specifica sezione a conclusione della parte quinta, „Delle ombrosità e chiarezze dei monti‟, capitoli 791-821, che in altre parti, ad esempio nel capitolo 149 che si rifà al 794; il capitolo 243, „Da chi nasce l’azzurro dell’aria‟, strettamente legato alla sopracitata pagina del Codice ex Leicester; nel capitolo 260, „Del colore delle montagne‟; nei capitoli 518 e 519 che si riferiscono alla visione lontana dei monti rispettivamente da un punto elevato e dal basso; nel capitolo 747 relativo alle ombre di una montagna. Queste formulazioni sono il frutto di una personale esperienza sulle Alpi. Solo da questa avrebbe potuto dedurre la principale osservazione dalla quale conseguono la maggior parte delle tesi esposte: la densità e la temperatura dell’aria diminuiscono con l’altezza (capitolo 799), con la duplice conseguenza nei riguardi sia della visione della montagna con le variazioni di luci, ombre e colori a seconda dei diversi piani visivi che dell’aspetto della natura alpina, con il mutamento dei caratteri della vegetazione e dei fenomeni meteorologici con l’altitudine.

Infatti nei capitoli 804, 805, 806 l’interesse è rivolto anche all’aspetto fisico e naturalistico dell’ambiente alpino. In essi, con formulazioni in diretto rapporto con quelle del Codice ex Leicester, si evocano con efficaci immagini l’erosione degli agenti atmosferici che determinano la forma delle montagne, i fiumi che erodono le valli, i laghi di sbarramento causati da frane e poi il singolare carattere dalla vegetazione alpina, la patina „ruginosa‟ (8) e l’effetto dei fulmini sulle rocce in alta montagna. I testi del Libro di Pittura sovramenzionati hanno una data di compilazione che si è stimata vicina a quella attribuita ai disegni della Serie Rossa, il 1511(9). Ebbene in questa serie tre, che hanno per soggetto paesaggi montani, sono certamente reali vedute alpine e non semplici studi preparatori per gli sfondi montuosi delle sue massime opere pittoriche. Sono tre piccoli fogli rettangolari poco più grandi di una cartolina, di carta preparata con un fondo di tempera rossa su cui con segno fermo e preciso Leonardo ha delineato creste, pareti, valloni, guglie con una attenzione alla morfologia montana mai prima riscontrata. Sono da considerare i primi veri ritratti delle Alpi. Nella storia della pittura si può citare un solo precedente: La pesca miracolosa del 1444, un dipinto del pittore tardo-gotico Konrad Witz(10). Infatti in esso la scena evangelica è ambientata sulle rive del lago di Ginevra e sullo sfondo si scorgono le vette ghiacciate del Monte Bianco. Ma in questo pur bellissimo olio le montagne sono solo scenografia lontana che risente ancora delle stilizzazioni gotiche, mentre nei disegni di Leonardo il paesaggio montano non è sfondo, bensì il soggetto principale, e ciò che soprattutto ci colpisce è il realismo e l’efficacia con cui lo delinea. In questi disegni si rivela quasi più lo scienziato che l’artista e sono il frutto di quella nuova sensibilità di approccio verso la realtà fisica che molto più avanti porterà al „metodo scientifico‟. L’esecuzione è infatti condotta con il massimo rispetto della realtà, quasi a suggerire una ripresa „fotografica‟. Forme, luci e ombre sono talmente fedeli che permettono una sicura identificazione non solo delle montagne, ma anche del luogo da cui sono state riprese e persino del momento del giorno e forse anche della stagione. Questo tipo di ripresa „fotografica‟ ha un diretto riferimento nel Libro di Pittura. Già nei capitoli 100, 97 e 90 si analizza la tecnica di ripresa dal vero, proponendo vari aiuti tecnici, dal filo a piombo, al reticolo tra l’oggetto e l’occhio, allo schermo trasparente su cui delineare l’immagine vista con un solo occhio (o attraverso un piccolo foro come nel famoso prospettografo disegnato sul Codice Atlantico). Nel capitolo 797 si affronta poi il problema della ripresa di una immagine lontana e della difficoltà di individuare le reali dimensioni di oggetti lontani. Si suggerisce l’individuazione di un campo visivo (che risulta di circa 25°) ottenuto distanziando di mezzo braccio dall’occhio una „finestra‟ di un quarto di braccio (15 cm) che lo delimiti, e uguale a questa „finestra‟ deve essere la dimensione del dipinto stesso. Ciò concorda col fatto che, sia nella Serie Rossa che in quella dell’Adda, paesaggi e vedute sono eseguiti su fogli di analoghe dimensioni. Si ritornerà più avanti ad analizzare una particolarità probabilmente legata alla tecnica di ripresa.

Caratteristico in questi disegni è il „segno‟ preciso e analitico con cui Leonardo ha potuto disegnare minuscoli particolari spesso apprezzabili solo con una lente. È proprio il „segno‟ che riscontriamo anche nei suoi studi di anatomia o meccanica o idraulica ed è uno strumento essenziale del suo metodo d‟indagine e del suo approfondimento della realtà fisica. La ragione per cui le montagne di Leonardo ci appaiono così vere è che egli è il primo pittore che ne ha studiato a fondo la morfologia e la natura geologica, proprio come non sarebbe possibile ritrarre efficacemente e realisticamente un corpo umano non conoscendo l’anatomia.

Questo incontro tra arte e natura è la testimonianza dell’inizio del rapporto tra le Alpi e la cultura occidentale che, come ha ampiamente illustrato Philippe Joutard(11). affonda le sue radici nella creatività figurativa del Rinascimento, per maturare lentamente con il contributo di artisti, umanisti, storici e naturalisti del Cinque e Seicento sino alla stagione dell’Illuminismo, coronata dalla conquista del Monte Bianco.

I TRE disegni che considereremo sono ora nelle Collezioni Reali di Windsor e catalogati come RL 12410 (10,5×16 cm), RL 12414 (15,9×24 cm) e RL 12411-12413 (5,4×18,2 cm; 7,2×14,7 cm). Pubblicati innumerevoli volte sia in libri sull’opera di Leonardo, (12) sia in studi sul rapporto tra Leonardo e le Alpi e in varie monografie su Monte Rosa, Monte Bianco o sui Panorami alpini, (13) sono quindi ben noti anche nell’ambito di chi si interessa di cultura alpina e di storia dell’alpinismo. Ma nonostante si fosse già da tempo indirizzati verso una corretta individuazione dei soggetti(14), si è tornati recentemente a vedervi le vette innevate del Monte Rosa. (15) In queste note desidero quindi dare una interpretazione sicura, argomentata e definitiva di questi disegni, fornendo di essi una dettagliata e certa descrizione dei soggetti ed una individuazione del punto di ripresa.

Alla base dei risultati positivi di questa ricerca c’è semplicemente la conoscenza e la lunga familiarità col profilo delle Alpi da Milano e coi paesaggi delle Grigne e delle Prealpi lombarde. Quando apparve il libro di Virgilio Ricci sulle esperienze alpine di Leonardo e vidi per la prima volta quei disegni, vi riconobbi subito i reali soggetti, come fossero i volti di persone conosciute. Per uno storico o critico d‟arte che non abbia avuto familiarità con i profili delle Alpi sarebbe stato difficile arrivare all’esatta conclusione.

Il foglio catalogato RL 12410 è il più noto, perché studiato e pubblicato più frequentemente, certamente per la sua più accurata esecuzione. In esso si distinguono tre soggetti: (a) un lungo panorama che si estende nella parte centrale, (b) un piccolo schizzo nella parte centrale inferiore e (c) un panorama meno esteso nella parte superiore destra. Quasi sempre sono stati indicati come „alte vette alpine coperte di neve‟ a volte „emergenti da un mare di nuvole‟ e riferiti al Monviso o, soprattutto, al Monte Rosa(16); certamente per l’influenza delle annotazioni sul Codice ex Leicester relative al „mon Boso‟, identificato dai più con il Monte Rosa. Il solo Carlo Pedretti giustamente dissente: „eppure nel disegno centrale si intravede un accenno alla pianura sottostante: non si tratta dunque di vette al di sopra di banchi di nuvole, ma dello stesso tipo di montagna rappresentato in RL 12414‟, cioè montagne „del paesaggio nei dintorni del Lago di Como a nord di Lecco‟(17). Ed è proprio così, ma di certo non si sospettava il sorprendente punto di osservazione. Furono infatti tutti eseguiti da un punto situato nel centro di Milano e Leonardo dedicò alla loro esecuzione l’intero arco della giornata. Forse osservò le montagne da qualche torrione del Castello Sforzesco, oppure – e quale migliore vedetta si può immaginare – dal tetto del costruendo Duomo, un luogo da lui certamente frequentato per il suo documentato progetto di tiburio. Questo stesso luogo è divenuto poi celebre per osservare il panorama delle Alpi. Nei Tour descritti dai Baedeker dell’Ottocento era considerato una tappa obbligata(18).

I tre soggetti che Leonardo disegnò rappresentano: (a) una veduta delle Prealpi lecchesi che va dal Cornizzolo (a sinistra) al Pizzo dei Tre Signori (a destra) con al centro le due piramidi gemelle delle Grigne; (b) un particolare del settore centrale di (a); (c) il Pizzo Arera nelle Prealpi bergamasche. La precisione e il dettaglio sono stupefacenti, Leonardo quasi sessantenne doveva essere dotato di una vista acutissima. In (a) si riconoscono molte vette; le più evidenti, da sinistra: il Cornizzolo, con ben individuati e delineati i valloni del versante meridionale; il monte Croce; con minore chiarezza i Corni di Canzo; poi l’emergente piramide sommitale del Legnone con il versante sud-est illuminato dal sole mattutino – ben evidente in (a) la luce proveniente da destra – quindi la vetta del Grignone, si noti illuminato il liscio versante sud-est; poi la Grignetta con a metà della cresta a destra i Torrioni Magnaghi; quindi il Pizzo Rotondo e il monte Melaccio; in basso, sorgente dalla pianura ed evidenziato in primo piano, il monte Due Mani; esattamente poco sopra si distinguono – incredibile – due punte del Pizzo Varrone e infine il Pizzo dei Tre Signori. In (b) Leonardo ridisegnò il tratto superiore di panorama che va dal Legnone al Grignone, quindi è da escludere la „maraviglia‟ di „vette emergenti da un mare di nuvole‟. (19) Osservando poi i versanti illuminati – luce proveniente da sinistra – si deduce che fu ripreso nel tardo pomeriggio, quando il sole radente evidenzia i particolari. Spiccano il Sasso dei Carbonari e il Sasso Cavallo, (20) che Leonardo vide da vicino essendosi inoltrato, come scrisse nel Codice Atlantico, (21) sopra Mandello del Lario a visitare la grotta della Ferrera in val Meria(22) che si apre ai loro piedi. Queste „montagne di mandello‟ le definì giustamente „i maggior sassi scoperti che si trovino in questo paese‟, riferendosi non tanto all’altezza assoluta, inferiore a quella del Legnone, ma alla dimensione delle strutture rocciose, per la quale nella regione non hanno rivali. La posizione relativa del Legnone, che in realtà si trova 16 km più a nord delle Grigne, ci fornisce un‟ulteriore conferma del punto di ripresa del panorama. È infatti sufficiente spostarsi di un chilometro a est o a ovest dal centro di Milano per veder nascondersi il Legnone dietro il Grignone o farsi sovrapporre dal monte Croce. E quindi quale se non il Duomo – che sorgeva dominando la città come una colossale montagna di marmo e su cui Leonardo avrà certamente fatto lunghi sopralluoghi per il suo progetto di tiburio – poteva essere un ideale punto di osservazione?

In (c) si individua ben delineato il solo Pizzo Arera, con appena abbozzata la cima di Menna a sinistra. Come mai questa montagna, non certo molto più evidente di altre, e certamente molto meno del Monte Rosa, quando questo è visibile da Milano? Forse la ragione è che, come per le pareti delle Grigne, le sue forme gli erano note, anzi familiari. Infatti nei frequenti viaggi a Vaprio lo poteva osservare di fronte a sé, trovandosi rispetto a Milano giusto nella direzione di Vaprio. Proprio come ora il Pizzo Arera, nelle giornate limpide, fa da quasi surreale sfondo a via Padova e dovrebbe essere familiare ai non disattenti frequentatori di questa via sempre congestionata. Ancora oggi la si percorre per imboccare la Statale Padana Superiore che conduce a Vaprio.

Un’altra osservazione riguarda la lumeggiatura di biacca su alcuni versanti e sulle creste. Probabilmente le montagne avevano subìto una spruzzata di neve e si era quindi nella stagione invernale o primaverile. Ciò è possibile, essendo questi i migliori periodi per osservare le Alpi da Milano: in tali stagioni quando è sereno l’aria è più limpida, inoltre con luci più radenti e una spruzzata di neve i dettagli sono evidenziati maggiormente. Un particolare che potrebbe sfuggire lo si rileva osservando anche alcune ottime e ingrandite riproduzioni. Nel panorama centrale, all’estrema sinistra del foglio emergente dalla cresta occidentale del Cornizzolo, accennata con un segno molto leggero, è disegnata un‟alta montagna a forma triangolare: essa corrisponde esattamente al Pizzo Stella, la bella vetta a nord di Chiavenna. Trovandosi sullo spartiacque principale delle Alpi è visibile con più difficoltà, perché quando si verificano le condizioni meteorologiche favorevoli – vento da nord – le montagne dello spartiacque sono spesso coperte da nubi.

Infine un’ipotesi sulla tecnica di ripresa suggerita sia dall’estrema precisione nel dettaglio, sia dalla constatazione che nel disegno i rilievi montani sono più slanciati che nella realtà. Sovrapponendo il disegno ad una foto si può constatare la perfetta collimazione – entro il millimetro – della posizione delle vette e di contro una evidente accentuazione della scala verticale nel disegno. Ciò suggerisce l’impiego da parte di Leonardo o di una tecnica di ripresa descritta nei citati capitoli del Libro di Pittura o anche del prospettografo disegnato nel Codice Atlantico, (23) con la particolarità che il vetro su cui è proiettata l’immagine da rilevare non sia stato verticale, ma leggermente inclinato, con la conseguenza di allungare la dimensione verticale. Un altro panorama alpino disegnato da Leonardo è quello delineato sul foglio RL 12414. In verità sul foglio ve ne sono due, dei quali il superiore poco più che abbozzato e l’inferiore più rifinito. La minor cura che si nota rispetto a RL 12410 ci fa pensare a schizzi presi durante un viaggio. La conferma di ciò la fornisce anche il soggetto sul foglio composto dai due frammenti RL 12411 e 12413. Questi disegni potrebbero infatti illustrare una sorta di „viaggio pittoresco lungo la riva occidentale dell’Adda‟, essendovi ritratte le Prealpi lecchesi riprese da punti molto prossimi alla riva milanese dell’Adda.

Chissà, forse Leonardo stava effettuando sopralluoghi per i suoi studi idraulici del Naviglio di Paderno, di cui aveva progettato la famosa chiusa, o stava soltanto effettuando una semplice escursione. Sul foglio RL 12414, il soggetto principale è il panorama delle Prealpi lecchesi nel tratto che va dalle Grigne (a sinistra) all’Albenza (a destra) ed è stato ripreso sul ciglio occidentale del profondo canyon dell’Adda in una località circa 2 km a monte di Trezzo, e quindi a soli 6 km dalla villa Melzi di Vaprio, presso la quale Leonardo fu lungamente ospitato. Procedendo da destra riconosciamo la lunga costiera dell’Albenza con ben delineati i vari costoni che scendono a sud-ovest; poi il monte Tesoro precede l’accidentato profilo del Resegone, che da qui si presenta assai di profilo e quindi, oltre il solco della Valsassina, ecco il liscio versante sud-est del Grignone e l’accidentata Grignetta con le sue guglie e infine a sinistra contro il cielo ecco la cresta ovest. Chiamata „Cresta Segantini‟ e molto frequentata dagli alpinisti lombardi, è fedelissimamente delineata con gli adiacenti torrioni, tra i quali si distingue certamente la possente Torre Cecilia. Il lungo crinale con macchie di alberi che si estende per tutta la lunghezza del foglio, coprendo le basi delle montagne sopraindicate, e che ha la sua sommità in corrispondenza del Resegone, è il monte Canto, alla cui base meridionale c‟è Sotto il Monte Giovanni XXIII, e a quella settentrionale la Pontida del famoso giuramento. Questa altura, che si trova scostata alcuni chilometri più a sud della catena principale, ci permette di individuare l’esatto punto di osservazione di Leonardo, che è quello da cui la sua sommità si posiziona sotto la vetta del Resegone. Anche in questo caso il panorama reale è alquanto più „piatto‟. Anzi qui la differenza è molto più marcata, tanto da rendere non evidente al primo sguardo la corrispondenza tra disegno e foto. Mentre nel caso di RL 12410 la distanza con lo scenario disegnato è superiore ai 50 km (il campo visivo è circa 15°), qui le montagne sono assai più vicine – le pendici dell’Albenza sorgono a 15 km. Ne consegue che il campo visivo, per poter contenere un tratto significativo di panorama, deve essere assai più ampio (circa 45°). Ma nonostante Leonardo abbia usato un foglio più grande ha dovuto, in modo molto più evidente che in RL 12410, accentuare la scala verticale e restringere quella orizzontale. Per la notevole selvatichezza del luogo (ancora oggi è difficile trovare tra la fitta vegetazione un pertugio per osservare la veduta) è assai improbabile in questo caso l’uso delle sopracitate tecniche di ripresa.

Nella parte superiore destra del foglio si osserva una serie di schizzi. Una cima dalle forme slanciate sulla sinistra potrebbe essere il M. Barro visto da SSO. Si rilevano alcune colline di cui una sormontata da una torre che potrebbe essere la collina di Montevecchia o il colle Brianza con il famoso Campanone, l’antica torre di Teodolinda allora ancora integra. Ma non sarebbero compatibili con le più elevate montagne schizzate sullo sfondo. Queste sono da identificare ancora con le Grigne: sono infatti riconoscibili le linee accidentate della Grignetta, sopra la quale emerge la cresta più regolare del Grignone e, più a destra ancora, si individuano i profili del Resegone e del monte Tesoro, tutti ripresi da una posizione non molto diversa da quella della veduta principale. L’aspetto prealpino di queste vedute, messo in evidenza dalle lunghe creste ondulate, era stato individuato da quasi tutti i commentatori, (24) con l’eccezione di una attribuzione al solito Monte Rosa ritratto nientemeno che dall’alpe Bors in Val Sesia.(25)

Il testo scritto nel margine inferiore del foglio si riferisce al colore e all’atmosfera azzurrina che avvolge le montagne, soprattutto nelle loro zone d‟ombra e all’influenza della vegetazione e delle pietre nel colore delle montagne. Recentemente decifrata con l’aiuto della fotografia a raggi infrarossi, è in sintonia con analoghi testi del Libro di Pittura. (26) Notiamo infine che rispetto ai tempi di Leonardo qualcosa, purtroppo in peggio, è cambiato: ora l’Albenza, come pure il Cornizzolo, oltre ad essere deturpati da numerose antenne sono devastati da colossali cave che alimentano i vicini cementifici. Così il buchetto che Leonardo aveva fatto per cavare qualche „nicchio‟, e che mise in gran subbuglio i sospettosi abitanti del luogo (27) è diventato un immane baratro in perenne aumento.

La terza veduta, quella disegnata sul foglio composto dai due frammenti catalogati RL 12411 e 12413, è l’unica che finora sia stata individuata. Rappresenta infatti, come prudentemente afferma Carlo Pedretti „un profilo scabroso, caratteristico delle montagne sopra Lecco, cioè il noto Resegone, che si riconosce probabilmente nel disegno ricostruito […]‟. (28) Sì, proprio il monte oggetto del famoso lapsus carducciano! In un lapsus ancora più evidente si incorre laddove viene negata questa corretta identificazione, attribuendola alla regione del solito Monte Rosa, (29) astenendosi però dal precisare il soggetto e il punto di osservazione. Questo è invece esattamente individuabile sulla Rocchetta presso Airuno, una caratteristica sommità panoramica che sovrasta l’ampio meandro dell’Adda, di cui si intravede nella parte inferiore del disegno il corso tortuoso fiancheggiato da alberi. Già avamposto della Repubblica Veneta, questa altura strategica fu annessa al Ducato di Milano nel 1450. Ora vi sorge un pittoresco Santuario e dal suo bel porticato si ha una estesa veduta sulla valle dell’Adda e sulle Prealpi dalle Grigne, al Resegone e all’Albenza.

MOLTI ALTRI disegni di Leonardo hanno per soggetto montagne, per lo più rocciose. Ritengo però si debbano considerare studi preparatori per gli sfondi delle sue importanti opere pittoriche e non riprese dal vero. Anche il drammatico paesaggio alpestre con temporale in RL 12409, dove in una conca racchiusa da alte montagne rocciose è posto un agglomerato urbano, è un paesaggio di certo frutto di fantasia, pur se ispirato dalle numerose reali esperienze vissute in ambienti alpini e prealpini. In esso la forma e la disposizione delle montagne hanno un „passo‟ e una „scala‟ che rispondono più alla libera creazione e che ritroviamo simili in RL 12405. Basta un semplice confronto con i tre fogli che sono stati qui analizzati per convincersi che solo questi sono certamente studi dal vero: in essi il „segno‟ è netto, essenziale e analitico, negli altri è sfumato, più finalizzato a esigenze creative che documentarie.

Dunque, sono delle Prealpi lombarde i veri „ritratti‟ delle Alpi di Leonardo. La relativa vicinanza di questi monti con le sue residenze di Milano e Vaprio, l’averne percorso le pendici, visitate le contigue valli, i boschi, le miniere e le curiosità naturali ha sicuramente lasciato nell’animo suo un dolce sentimento di familiarità. Una sensazione che si rinnova in tutti coloro che amano le montagne quando le ravvisano da lontano. Leonardo nel 1511, ormai verso la vecchiaia, scorgendole da Milano in una limpida giornata di sole, o durante una gita lungo l’Adda ha fissato il ricordo di lontane esperienze, forse anche avventure, su quei fogli di sanguigna che, per le loro dimensioni, sono stati simpaticamente definiti cartoline-souvenir.(30) Un certo rammarico ci coglie se pensiamo invece alla mancanza, almeno finora, di testimonianze grafiche della così misteriosa e affascinante salita al „mon Boso‟. Il tentativo di associare i disegni della Serie Rossa a questa ascensione si è quindi rivelato vano. Se alla galleria dei ritratti del Monte Rosa sono venuti a mancare questi nobili esemplari d‟Autore al nostro gigante alpino non importerà poi gran che, la su grandezza e il suo fascino erano già grandi e tali sono rimasti. Ma in compenso ai poveri, modesti, martoriati e violentati Cornizzolo e Albenza verrà almeno un piccolo fremito d’orgoglio.

(pubblicato in “Achademia Leonardi Vinci, Journal of Leonardo Studies & Bibliography of Vinciana”,Vol X, 1997, pp. 125-133, 8 pp. di tav. f. t.)

NOTE

1 Gerolamo Calvi, Vita di Leonardo, Brescia, 1936, p. 58. Pubblicazione postuma recensita da Enrico Carusi in«Raccolta Vinciana», XV-XVI, 1935-1939, pp. 321-23.

2 L’interesse per le Alpi in Italia rimase, dopo Leonardo, a lungo assopito. A nord delle Alpi invece si mantenne vivo, sia pure in una stretta cerchia di storici e umanisti (Aegidius Tschudi, De prisca ac vera Alpina Rhaetia, Basilea, 1538; Josias Simler, Vallesiae Descriptio – De Alpibus Commentarius, Zurigo, 1574; Ulrich Campell, Rhaetia Alpestris topographica descriptio), nei cui testi, che sono i principali nel XVI secolo, non si riportano solo dati attinti da fonti classiche, ma anche notizie e informazioni da esperienze dirette o da contemporanei. Ciò che invece non accade nei nostri Flavio Biondo (Italia Illustrata, 1451), o Leandro Alberti (Descrittione di tutta Italia …, Bologna, 1550), o Gaudenzio Merula (Gallorum Cisalpinorum antiquitate ac origine, Bergamo, 1592). Anche nelle arti figurative le Alpi sono un soggetto soprattutto per artisti dell’area nordica, come Dürer, Altdorfer, Pieter Bruegel. Una eccezione è Tiziano che, nato nel cuore delle Dolomiti del Cadore, talvolta sembra ricordarsi dei paesaggi della sua infanzia, come nello sfondo della Presentazione della Vergine al tempio. È col XVIII secolo che l’interesse diviene sempre più crescente, iniziando da J. J. Scheuchzer, Itinera Alpina …, Londra, 1708 (2a ed., Leida, 1723), Albrecht von Haller, Die Alpen, Berna, 1732, un poema che, tradotto in varie lingue (italiana nel 1768, Yvérdon), ebbe vastissima diffusione e costituì un elemento decisivo per la definitiva ‘scoperta’ del mondo alpino, così pure il romanzo epistolare di J. J. Rousseau, La Nouvelle Héloïse, 1761. Si giunge quindi alle opere di carattere scientifico-geografico di J. G. Altmann e di G. S. Gruner sui ghiacciai alpini, dei fratelli Deluc, di M. T. Bourrit e soprattutto di H. B. de Saussure, il promotore della prima ascensione del Monte Bianco (di Gabriel Paccard e Jacques Balmat nel 1786) e autore dei Voyages dans les Alpes, 4 voll., Neuchâtel, Ginevra, 1779-96, che schiude definitivamente le porte delle Alpi alla conoscenza universale. A sud delle Alpi sono soprattutto botanici e naturalisti che si addentrano timidamente nelle valli alpine. Ma per trovare una testimonianza figurativa che, dopo Leonardo, riguardi significativamente le Alpi bisogna attendere la metà del XVIII secolo (1744) con il quadro di Bernardo Bellotto, Veduta di Gazzada e della Villa Melzi d’Eril, che ha sullo sfondo la catena alpina e il Monte Rosa. Basta tuttavia osservare la differenza tra la precisione del dettaglio nei primi piani e la sommaria definizione della catena alpina per avvertire l’inadeguatezza della lettura e della comprensione del paesaggio alpino che si aveva allora. Dalla seconda metà del XVIII secolo, anche in Italia inizia un interesse più diffuso. Lo testimoniano le esplorazioni di alcuni intrepidi giovani di Gressoney nel 1778, 1779 e 1780, alla testata della loro valle, ancora avvolte in un’aura quasi leggendaria. Gli astronomi Padre Beccaria e successivamente Barnaba Oriani nel 1788, in occasione di triangolazioni geodetiche da Torino e da Milano, misurano l’altezza del Monte Rosa. De Saussure magnifica la veduta delle Alpi da Torino e Vercelli e visita le valli meridionali del Monte Rosa nel 1789, di poco preceduto, nel 1785 a Macugnaga, da Carlo Lodovico Morozzo della Rocca. Nicolis di Robilant pubblica, nel 1790, i risultati dei suoi viaggi nelle zone metallifere del Piemonte con ampie descrizioni e numerose vedute. Del medico Pietro Giordani di Alagna Valsesia è la prima ascensione, nel 1801, a un’alta cima del Monte Rosa. L’accurato studio di

Ludwig Von Welden, Der Monte Rosa, Vienna, 1824 (traduzione con introduzione curata dalla Fondazione Monti, Anzola d’Ossola 1987), riassume e conclude, con un lavoro che per importanza si affianca a quello di De Saussure, la fase dei pionieri aprendo da sud le vie delle Alpi non solo a naturalisti e studiosi, ma anche ai turisti e agli alpinisti. Von Welden, a lungo residente a Milano al seguito dell’esercito austriaco e protagonista nelle prime vicende risorgimentali, fu affascinato dalla visione delle Alpi dalla pianura padana e in particolare dalle imponenti ed eleganti linee del Monte Rosa.

3 CA, f. 214 r-e, c. 1490-2 (Richter, § 1030).

4 Ivi. Un’illustrazione di questo documento è in Mario Cermenati, Leonardo in Valsassina, Milano, 1910.

5 Cod. ex Leicester, Carta 4A, f. 4 r.

6 Sia Gustavo Uzielli, Leonardo da Vinci e le Alpi, in «Bollettino dei Club Alpino Italiano», XXIII, 1890, pp. 81-156, sia Virgilio Ricci, L’andata di Leonardo da Vinci al Mon Boso …, Roma, 1977, deducono dall’analisi della cartografia storica che si tratti del Monte Rosa. Al tempo di Leonardo (e sin dal XIV sec.) con tale toponimo era indicato il Monte Rosa, specialmente dal versante valsesiano. Di opinione contraria Douglas W. Freshfield, The Alpine Notes of Leonardo da Vinci, in «Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society», VI, 1884, pp.335-40, favorevole dapprima ad una identificazione con il Monviso e in seguito a quella col Monte Bo. Anche Coolidge e recentemente Joutard identificano il Monboso col M. Bo. Su dove effettivamente Leonardo sia salito la mancanza di effettivi riscontri lascia tuttora il campo aperto a varie ipotesi. Se comunque è da escludere la salita alle cime massime del Monte Rosa, avvicinate solo alla fine del XVIII sec. e salite tra il 1819 e il 1861, varie sono le possibilità sia sulle alte regioni, prossime alle zone pascolive, che sui numerosi e meno elevati colli e cime che gli fanno corona.

7 Leonardo da Vinci, Libro di Pittura. Ediz. in facsimile a cura di Carlo Pedretti. Trascr. critica di Carlo Vecce, Firenze, 1995.

8 La patina di colore ruggine delle rocce in alta montagna è anche causato da alcuni tipi di licheni.

9 La datazione della Serie Rossa è resa possibile dalle note leggibili sul disegno RL 12416. Melzi trascrisse a penna sul medesimo foglio le note originali di Leonardo a matita rossa, ormai deterioratesi. Esse sono: ‘Addì 16 di dicembre a ore 15 fu acceso il fuocho’ e ‘Addì 18 di dicembre 1511, a hore 15, fu fatto questo secondo incendio da Suizeri presso a Milano al luogo dicto Dexe’. Leonardo fu quindi testimone del fallito tentativo dell’esercito svizzero di occupare Milano, in mano francese, per insediarvi Massimiliano, figlio di Lodovico Sforza. In quell’azione militare, ricordata dal cronista Prato (Storia di Milano scritta da Giovanni Andrea Prato, Firenze, 1842, pp. 286-87), la città fu posta sotto assedio il 14 dicembre. Gli svizzeri, in difficoltà di vettovagliamento, furono convinti in una brevissima trattativa a togliere l’assedio e tornare oltralpe. Purtroppo non senza aver prima saccheggiato e incendiato quasi tutti gli abitati a nord di Milano, a iniziare da Bresso, poi Affori, Niguarda, i più vicini, quindi Cinisello, Desio, Barlassina e Meda, seguendo il corso della ritirata. Gli incendi osservati da Leonardo probabilmente si riferiscono a quelli degli abitati, poiché in quella stagione i campi o erano stati appena arati o erano privi di vegetazione. La presenza nel foglio dei due soggetti accompagnati dalle due annotazioni fa pensare a una registrazione ‘in diretta’ dell’avvenimento, ma da dove? Poiché Desio, con cui si identifica ‘Dexe’, dista in linea d’aria 26 km a ovest da Vaprio d’Adda, è da escludere che Leonardo abbia potato osservare e disegnare dalla Villa Melzi con simile dettaglio i due incendi raffigurati. Né d’altra parte si può pensare che Leonardo, come un audacissimo fotoreporter di guerra dei giorni nostri, si aggirasse impavido con la sua cartella di fogli preparati a sanguigna nel territorio lombardo, devastato da sanguinarie milizie mercenarie. È quindi verosimile ipotizzare la sicura e ben munita Milano come punto di osservazione. Ma anche da qui Desio, che in linea d’aria dista ben 16 km a nord, non avrebbe potuto apparire come nel disegno. Ne consegue che probabilmente non si tratta di Desio, ma di località più prossime a Milano. La prima, il giorno 16, potrebbe essere Bresso, la prima nell’elenco del cronista Prato. È distante solo 7 km a nord e con essa, accomunata in un analogo destino, il giorno 18, anche la località di Niguarda più ancora vicina, 5 km, situata per un osservatore da Milano un poco più a destra, come nel disegno. Poiché nel testo di Leonardo rimasto leggibile non è presente una indicazione topografica non siamo certi che quella data da Melzi sia la trascrizione di quella originale o sia una sua molto posteriore aggiunta. Notiamo che la cronaca del Prato da una conferma delle date 16 e 18 dicembre, rispetto a 10 e 13 dicembre interpretate precedentemente. Il disegno è analizzato da Carlo Pedretti, in The Drawings and Miscellaneous Papers of Leonardo da Vinci in the Collection of Her Majesty The Queen at Windsor Castle. Volume I. Landscapes …, Londra, 1982, pp. 79 e 83-84.

10 Rottweil 1400-10, Basilea 1445-6. Cfr. Emil Maurer, in Enciclopedia Universale dell’Arte, XIV. 871-4 (con bibliografia aggiornata).

11 Philippe Joutard, L’invenzione del Monte Bianco. Traduzione ed introduzione di Pietro Crivellaro, Torino, 1993. Importante ed originale, specie per la metodologia, storia del rapporto tra montagna e cultura occidentale dal Rinascimento alla conquista del Monte Bianco.

12 Il Corpus dei disegni di Leonardo è stato illustrato e studiato da Carlo Pedretti, in The Drawings and Miscettaneous Papers of Leonardo da Vinci in the Collection of Her Majesty The Queen at Windsor Castle. Vol I. Landscapes …, Londra, New York, 1982, abbreviato in Windsor Landscape. Ulteriori precisazioni nel catalogo della mostra effettuata a Milano: Carlo Pedretti, Kenneth Clark, Leonardo da Vinci Studi di Natura dalla Biblioteca Reale nel Castello di Windsor, Firenze, 1982; e nel saggio di Carlo Pedretti, Leonardo e la lettura del Territorio in Lombardia: il territorio, l’ambiente e il paesaggio, a cura di Carlo Pirovano, Milano, 1981.

13 In Aldo Audisio, Bruno Guglielmotto-Ravet, Panorami delle Alpi dalla Pianura, Ivrea, 1979, è ben riprodotto e ingrandito il foglio 12410, che viene identificato con il Monviso; vi sono riprodotti anche i panorami delle Alpi dal Duomo di Milano dello Zucoli e del Bossoli. Anche in Franco Fini, Il Monte Rosa, Bologna, 1979, viene riprodotto il foglio 12410 ‘in cui forse L. ha raffigurato il M. Rosa’. In Ulrich Christoffel, La montagne dans la peinture, Club Alpin Suisse, 1963, vi sono riprodotti sia il foglio 12410 che La pesca miracolosa di Konrad Witz, così pure in Philippe Joutard, op. cit, e anche in E. W. Bredt, Die Alpen und ihre Maler, Leipzig, 1910, e AA.VV., Die Alpen in der Malerei, Rosenheim, 1981, che stranamente non citano l’importante quadro di Bernardo Bellotto.

14 In tutte le pubblicazioni di carattere alpinistico, pur recentissime, che si sono occupate di questi disegni non solo si sono fatte considerazioni errate, ma addirittura si sono rigettate ipotesi che invece indirizzavano alla via giusta. Carlo Pedrotti, in Windsor Landscape, è giunto assai più vicino alla corretta identificazione di coloro a cui la familiarità con le forme delle montagne avrebbe dovuto facilitare la soluzione del problema. Un contributo positivo lo offe anche Ipotesi e suggestioni. Mostra fotografica di disegni Vinciani e località lombarde, pubblicato dall’Ente Raccolta Vinciana, Milano s.d. (1995), catalogo che accompagna la mostra con foto di Luigi Conato. Nella mostra sono messi a confronto non solo i disegni della Serie Rossa, ma anche altri meno noti e alcune grandi opere pittoriche, con foto di paesaggi lombardi che potrebbero averli ispirati. I risultati della ricerca di Conato, per quanto concerne i disegni qui analizzati, in linea generale si avvicinano a quelli qui indicati nella individuazione dei soggetti, si differenziano invece nella localizzazione dei punti di ripresa. Ciò perché Conato li ritiene ripresi da Leonardo lungo la ‘Carraia del Ferro’, antico itinerario commerciale da Lecco a Milano che percorreva la Brianza, ed è a causa di questa non corretta ipotesi che non trova l’esatta concordanza che tra disegni e foto ho accertato nei punti da me indicati.

15 In AA.VV., Monte Rosa. La montagna dei Walser, Fondazione Monti, 1994, si incorre in un infortunio macroscopico, ed è stato accorgendomi di ciò che mi risolsi finalmente a scrivere queste note. Il volume contiene un ampio saggio di Luigi Zanzi su Leonardo alpinista e il Monte Rosa. In trenta pagine di grande formato (pp. 301-32) di prosa erudita, con le ottime riproduzioni a colori del ‘temporale alpino’ RL 12409 e dei tre fogli qui analizzati (attenzione però alle didascalie, dove i numeri di catalogazione di RL 12411-12413 e RL 12414 sono scambiati), si identificano questi come vedute del Monte Rosa effettuate da Leonardo (allora quasi sessantenne!) in una escursione-reportage alpina alquanto burrascosa (col temporale di RL 12409!) e certamente impegnativa (Colle del M Moro-Colle delle Locce-Colle del Turlo).

16 in Monte Rosa. La montagna dei Wlser, op. cit, p. 317, lo si definisce ‘il più autentico ritratto del M Rosa’!

17 Carlo Pedretti, Kenneth Clark, Leonardo da Vinci Studi di Natura dalla Biblioteca Reale nel Castello di Windsor, op. cit., p. 49, e Carlo Pedretti, Windsor Lanscapes, p. 75.

18 Possiamo infatti ricordare le testimonianze scritte e disegnate di Rodolphe Töpffer nei suoi Voyages en Zig Zag, di John Ruskin nel quinto volume di Modern Painters, dove riproduce un suo disegno del Monte Rosa

effettuato dal tetto del Duomo al tramonto, dopo un temporale estivo; e i dettagliati panorami della catena alpina da qui ripresi da Heinrich Keller, Leone Zucoli e da Edoardo Francesco Bossoli. Quello del Keller, disegnato sul Duomo nel 1816, inciso all’acquatinta da F. Schmid e pubblicato a Zürich da Füssli, è lineare e misura 165×1914 mm. È il primo che si conosca, il disegno è molto accurato, ma l’individuazione delle cime risente ancora dell’approssimativa conoscenza che in quell’epoca si aveva delle Alpi. Infatti vi sono nominati solo quarantaquattro monti, ma diciannove lo sono erroneamente. Il panorama disegnato e inciso da L. Zucoli e pubblicato da G. Pirola nel 1845 c., 422×420 mm, è invece circolare ma di modesto interesse per lo scarso dettaglio del disegno. Infine quello in litografia di E. F. Bossoli, pubblicato da G. Pirola nel 1878 è lineare e misura 135×1505 mm. È il più dettagliato e preciso essendoci oltre 180 indicazioni di toponimi alpini. Purtroppo non è conosciuto essendo diventato rarissimo. Bossoli fu uno specialista di panorami alpini e, tra il 1872 e il 1881, ne pubblicò una quindicina. Ricordiamo infine, del Bossoli, il Panorama delle Alpi Orobiche, ingrandimento di un limitato settore del panorama generale dal Duomo, che fu allegato alla guida di Antonio Curò, Guida alle Prealpi Bergamasche …, Milano, 1877. Ci interessa particolarmente perché vi è ben delineato il Pizzo Arera, cioè il medesimo monte disegnato da Leonardo in alto a destra di RL 12410.

19 Come indicato in AA.VV., Monte Rosa. La montagna dei Walser, op, cit., p. 314, e da altri.

20 Queste imponenti pareti rocciose alte 400 m sono ora ben note agli alpinisti perché vi sono tracciate alcune tra le più impegnative vie d’arrampicata.

21 CA, f. 214v.

22 Si tratta molto probabilmente della grotta della Ferrera (N° 1502 Lo Co dell’Inventario speleologico della Lombardia. Cfr. Natura in Lombardia: le grotte. Regione Lombardia, Milano, 1977, p. 180). Invece molti commentatori la identificano con la Ghiacciaia di Moncòdeno, (N° 1506 Lo Co, ad esempio V. Ricci, op. cit., p. 15; Mario Cermenati, La Ghiacciaia di Moncòdeno, in «Rivista del Club Alpino Italiano», 1899, p. 55, e anche gli autori dell’appena citato volume a p. 46). Ma Leonardo è sufficientemente chiaro nella localizzazione: ‘ … ma la [montagna] maggiore è quella di Mandello, la quale à nella sua basa una busa di verso il lago, la quale va sotto 200 scalini, e qui d’ogni tempo è diaccio e vento’ (CA, f. 214 v). La grotta della Ferrera, facilmente accessibile, è tra le maggiori e più note. Si apre alla quota 590 m proprio sotto le pareti del Sasso Cavallo e del Sasso dei Carbonari, quindi alla ‘basa’ della Grigna settentrionale, la più alta. Si trova nella Val Meria, valle che sfocia direttamente nel lago di Como (‘di verso il lago’) proprio a

Mandello. È costituita da un unico ambiente, una imponente sala lunga circa 180 m e larga 50 m, e scende per un dislivello di 37 m (e quindi proprio ‘va sotto 200 scalini’). L’accesso e la percorribilità interne sono facili, aiutandosi con una buona torcia. L’osservazione sulla presenza di ghiaccio, qui possibile solo fino alla primavera è l’unico elemento a favore della Ghiacciaia di Moncòdeno, ma questa si trova a 1640 m sul versante settentrionale che dà in Valsassina e quindi non ‘di verso il lago’, inoltre le dimensioni di questo ambiente ipogeo sono assai più modeste (30×25 m).

23 CA, f. 1 bis r-a (olim f. 386 v-a; nunc f. 5 r).

24 Carlo Pedretti, Kenneth Clark, Leonardo da Vinci Studi di Natura dalla Biblioteca Reale nel Castello di Windsor, op. cit., p. 49: ‘Il carattere delle montagne rocciose fa pensare al paesaggio dei dintorni del lago di Como a nord di Lecco’, che conferma quanto espresso in Carlo Pedretti, Windsor Landscape, op. cit., pp. 79, 85. Anche in V. Ricci, op. cit., p. 43: ‘rappresenta un gruppo di montagne dell’area prealpina, sicuramente di quella lombarda’.

25 In AA.VV., Monte Rosa. La montagna dei Walser, op. cit., p. 314, dove Alpe di Bors viene associato a ‘mon Boso”.

26 Carlo Pedretti, Windsor Landscapes, p. 85, e Leonardo e la lettura del territorio, op. cit,, pp. 252 e 263.

27 V. Ricci, op. cit, p. 13. Ad una cava di pietre sul monte Albenza fa diretto riferimento lo stesso Leonardo nel testo scritto nella parte inferiore del foglio: ‘vedesi alcuni liniamenti traenti al bianco, le quali son miniere dipietra [ …]’. Una cava in attività da cinquecento anni!

28 Carlo Pedretti, Kenneth Clark, Leonardo da Vinci Studi di Natura dalla Biblioteca Reale nel Castello di Windsor, op. cit., p. 48. In Carlo Pedretti Windsor Landscapes, la corretta deduzione è nell’introduzione di p. 79: ‘the rocky mountain called Resegone, possibly represented on 41 r’, e non a p. 87: ‘the range represents the Grigna over Lecco on Como Lake’.

29 In AA.VV., Monte Rosa. La montagna dei Walser, op. cit., p. 313.

30 Carlo Pedretti, Le ‘cartoline’ del Vinciano, in «Il Sole-24 Ore», 30 giugno 1996, p. 29.

ILLUSTRAZIONI / ILLUSTRATIONS

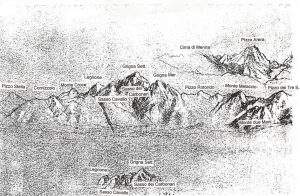

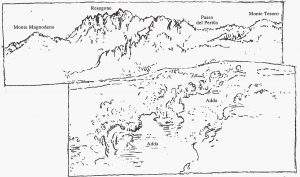

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

1 e 2. I soggetti di questo disegno, RL 12410 a volte attribuiti al Monviso e più frequentemente al M. Rosa si riferiscono in realtà alle Prealpi lombarde. Ben riconoscibili nel panorama centrale, con la luce del sole in arrivo da sinistra, dopo l’appena accennato P. Stella, il Cornizzolo, il M. Croce, la piramide sommitale del Legnone, le due Grigne, il P. Rotondo, e il M. Melaccio; più in primo piano il M. due Mani e all’estrema destra il Pizzo dei Tre Signori. Al centro in basso del foglio Leonardo disegnò il tratto tra il Legnone e la Grigna settentrionale, illuminato dal sole del tramonto, evidenziando le pareti del Sasso Cavallo e del Sasso dei Carbonari, a lui ben note. In alto a destra del foglio si riconosce la piramide del P. Arera. Cfr. fig. 4, 5, 13.

The subjects of this drawing, RL 12410, sometimes attributed to Monviso and more frequently to M. Rosa, refer in reality to the Lombard Prealps. Well recognizable in the central panorama, with the sunlight coming from the left, after the slightly drawn P. Stella, the Cornizzolo, the M. Croce, the top pyramid of Legnone, the two Grigne, the P. Rotondo, and the M. Melaccio; more in the foreground the M. due Mani and to the extreme right the Pizzo dei Tre Signori. At the center bottom of the sheet Leonardo drew the stretch between the Legnone and the northern Grigna, illuminated by the setting sun, highlighting the walls of the Sasso Cavallo and Sasso dei Carbonari, well known to him. At the top right of the sheet is the pyramid of P. Arera.

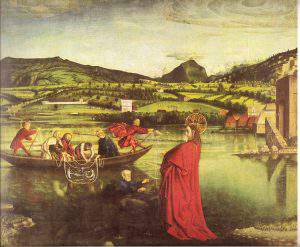

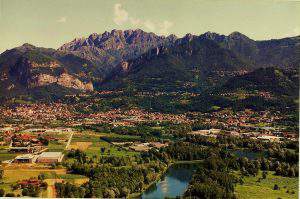

Fig. 3 Konrad Witz La pesca miracolosa 1444. Ginevra Musée d’Art et d’Histoire.

Fig. 4 Veduta delle prealpi lombarde dal tetto del Duomo di Milano con sovrapposto il particolare centrale del RL12410

Winter view of the Lombard Prealps from the roof of the Milan Cathedral with overlapping central detail of the RL12410

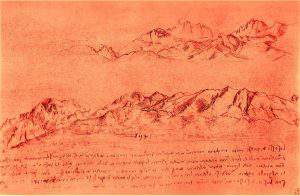

Fig. 5 e 6 Le prealpi Lecchesi e Bergamasche osservate dalla riva occidentale dell’Adda, a 2 Km a monte di Trezzo, sono il soggetto principale di questo foglio RL 12414. Da destra si riconoscono l’Albenza, il Monte Tesoro, il Resegone, il Grignone con il suo liscio versante SE e l’accidentata Grignetta con il dentellato profilo della cresta Segantini.

The Lombard Prealps observed from the west bank of the river Adda, 2 Km upstream of Trezzo, are the main subject of this sheet, RL 12414. From the right we can recognize the Albenza, Monte Tesoro, Resegone, Grignone with its smooth SE slope and the rough Grignetta with the serrated Segantini ridge profile.

Fig. 7 Prealpi Lecchesi e Bergamasche dal bordo occidentale del profondo canyon dell’Adda 2 Km a monte di Trezzo

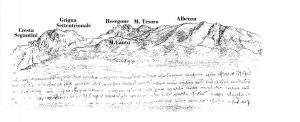

Fig. 8 – Ricostruito con due frammenti RL 12413 e RL 12414, Questo disegno raffigura il Resegone; nella parte inferiore si intravede il corso dell’Adda. Si confronti con l’illustrazione seguente, 9.

Reconstructed with two fragments RL 12413 and RL 12414, This drawing depicts the Resegone; in the lower part we can see the course of the river Adda. Compare with the following illustration

Fig. 9

Fig.10 – Veduta del Resegone e della valle dell’Adda dal Santuario della Rocchetta sopra Airuno,

si confronti con le figure precedenti.

View of Resegone and the river Adda valley from the Sanctuary of Rocchetta above Airuno, compare to previous figures.

Fig. 11 – Imbocco della grotta della Ferrera, si apre sul sentiero per il rif. Elisa nel gruppo delle Grigne, dominata dalle pareti del Sasso Cavallo e dei Carbonari. Leonardo la visitò rilevandone le giuste dimensioni

Entrance to the Ferrera cave, opens onto the path for the refuge Elisa in the Grigne group, dominated by the walls of Sasso Cavallo and the Carbonari. Leonardo visited it, noting the right dimensions

Fig 12- Il Sasso Cavallo a destra e il Sasso dei Carbonari addossati al Grignone dall’imbocco della Val Meria. Leonardo li definì “i maggior sassi scoperti che si trovino in questo paese” e tanto ne fu impressionato che ben li riconobbe osservandoli da Milano- Si confrontino le fig. 1, 2, 3.

The Sasso Cavallo on the right and the Sasso dei Carbonari leaning against Grignone from the entrance of Val Meria. Leonardo called them “the greatest bare rocks in this country” and was so impressed that he recognized them, well observing them from Milan.

Fig. 13 – L’imponente massa montuosa del M. Rosa da Milano in una limpida giornata. Testo della pagina del Codice Leicester con l’ascensione al Mon Boso

The imposing mountain mass of M. Rosa from Milan on a clear day. Text of the Leicester Code page with the ascent of the Mon Boso(Monte Rosa)

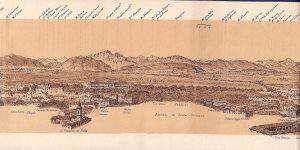

Fig 14 – Particolare del panorama dell’arco alpino dalla guglia del Duomo di Milano, rilevato da E. F. Bossoli e pubblicato nel 1878, nel tratto corrispondente a quello disegnato da Leonardo.

Detail of the panorama of the alpine arc from the highest spire of the Duomo of Milan, detected by E. F. Bossoli and published in 1878, in the section corresponding to the one drawn by Leonardo

Fig. 15 – “Le Alpi Orobiche disegnate da E. F. Bossoli dal Duomo di Milano” pubblicato nel 1877 nella “Guida delle Prealpi Bergamasche…” Si vedono ben delineati il Pizzo Arera e la Cima di Menna che Leonardo disegnò nella parte superiore destra di RL 12410. Si confronti la fig. 1

The Orobic Alps drawn by E. F. Bossoli from the Duomo of Milan, publishers in 1877 in “Guida delle Prealpi Bergamasche…” We can clearly see the Pizzo Arera and the Cima di Menna that Leonardo designed in the upper wright part of RL 12410. See fig. 1.

THE LOMBARD PREALPS PORTRAYED BY LEONARDO

By Angelo Recalcati

Essay published on vol. X, 1997 of Achademia Leonardi Vinci. Journal of Leonardo Studies and Bibliography of Vinciana Edited by Carlo Pedretti.

Work quoted in: La Sainte Anne. L’ultime chef-d’oeuvre de Léonard de Vinci. Edition Louvre 2012. pp. 155, 431.

In 1482 Leonardo at age thirty, left his native Tuscany and its sweet green hills of vineyards and cypresses to reached Milan in the middle of Valle Padana, a humid and fertile plain with long rows of poplars and mulberry trees immersed in the typical stagnant and foggy atmosphere. He arrived there on one of the odd days when the north wind was sweeping the mist, discovering the great mountain range of the Alps on the horizon. What a majestic sight! And, at the same time, what promising and stimulating new perspectives, new studies and new experiences.

This suggestive poetic image, suggested by Gerolamo Calvi (1), obviously has just a symbolic meaning, since there is no biographical reference to it. Yet, in more than twenty years which he spent in Milan, Leonardo certainly had the chance to become familiar with this vision which, even if unusual, occurs for many days every year. Now we are certain of this: in fact one of the most significant traits of this panorama was not only familiar to Leonardo, but interested him to the point of observing and studying it for a long time and fixing it in a drawing.

Leonardo was the first to look up at this grandiose crown of peaks, and only after almost three centuries other painters from the Po Valley, felt the wealth of knowledge, experience and beauty that the Alps could offer. (2)

The amazing profile of these rocky or snowy peaks , at that time unexplored, was certainly an incentive to undertake those “trips […] to be done in the month of May” (3) that will lead him to enter the area of the Prealps and Alps of Lombardy to which the notes in the Atlantic Code refer (4). In the Leicester Code (5) we have instead the account of his excursion in the high mountain, on the slopes of the “mon Boso”, the ancient name of Monte Rosa (6). Unlike in the Atlantic Code, where in some cases the annotations are so impersonal that they can be considered notes from news received from others, here Leonardo unequivocally emphasizes his direct experience. An experience that has deeply impressed him: the proof of an environment so much distant from those of everyday life is strengthened by the epic phrase: “and this will see, as I saw, who will go over mon Boso, summit of the Alps [ …]” almost to anticipate and completely legitimate doubts and disbelief, since the experience of reaching a high mountain will cease to be a rare and singular episode and becomes a common heritage only three centuries later. In this exciting page of the Leicester Code entitled “Of the color of the air” his two main interests meet and merge: Painting and Science. Two interests that in Leonardo grow and develop in symbiosis tending towards a form of total creative knowledge, a concept that finds its complete formulation in the “Libro di Pittura” (7).

TO THE VISION of the mountains Leonardo dedicates ample space in the “Libro di Pittura”(Book of Painting), both in the specific section at the end of the fifth part, “Of the shadows and clarity of the mountains“, chapters 791-821, and in other parts, for example in chapter 149 which refers to the 794; chapter 243, “From whom the blue of the air is born“, closely linked to the aforementioned page of the Leicester Code; in chapter 260, “Of the colour of the mountains“; in chapters 518 and 519 referring to the distant view of the mountains respectively from a high point and from below; in chapter 747 on the shadows of a mountain. These expressions are the result of a personal experience in the Alps. Only from this he could deduce the main observation from which most of the these statements are obtained: the density and the temperature of the air decrease with height (chapter 799), with the double consequence concerning both the vision of the mountain with the variations of lights, shadows and colors depending on the different visual perspectives and the appearance of the alpine nature, together with the change of the characteristics of the vegetation and meteorological phenomena of the altitude.

As a matter of fact, in the chapters 804, 805, 806 his interest is also turned towards the physical and naturalistic aspect of the alpine environment. In them, with quotes in direct relation with those of the Leicester Code, are evoked with vivid images, the erosion of atmospheric agents that determine the shape of the mountains, the rivers that erode the valleys, the barrage lakes caused by landslides and also the singular nature of the alpine vegetation and the effect of the lightning on the rocks of the higher mountains. The texts of the above-mentioned Book of Painting have a compilation date, on 1511, which is estimated to be close to that given to the “Red Serie” drawings (9). Well in this serie three drawings which have mountain landscapes as their subject, are certainly true alpine views and not simple preparatory studies for the mountainous backgrounds of his greatest pictorial works. They are three small rectangular sheets slightly larger than a postcard, made of paper with a red tempera primer on which, with a firm and precise mark, Leonardo has outlined ridges, walls, valleys, spires with an attention to the mountain morphology never encountered before. They are to be considered the first true portraits of the Alps. In the history of painting, only one precedent can be cited: “The miraculous fishing” of 1444, a painting by the late-Gothic painter Konrad Witz (10) where the evangelical scene is set on the shores of Lake Geneva and in the background, you can see the frozen peaks of Mont Blanc. But in this very beautiful oil painting the mountains are only distant scenography still influenced by Gothic styling, while in Leonardo’s drawings, the mountain landscape is not the background, but the main subject, and what strikes us most is the realism and effectiveness with which he outlines it. In these drawings, the scientist and the artist are almost invited to be the result of that new sensibility of approach to physical reality that will lead much further on to the “scientific method”. The execution is in fact conducted with the utmost respect for reality, as if to suggest a “photographic” shooting. Shapes, lights and shadows are so accurate that they allow a sure identification not only of the mountains, but also of the place from which they were taken and even the time of day and perhaps even the season. This type of “photographic” shooting has a direct reference in the Book of Painting. Already in chapters 100, 97 and 90 the technique of shooting from life is analyzed, proposing various technical aids, from the plumb line, to the lattice between the object and the eye, to the transparent screen on which to delineate the image seen with only one eye (or through a small hole like in the famous prospectograph drawn on the Atlantic Code). A characteristic of these drawings is the precise and analytical “sign” with which Leonardo has been able to draw small details that are often appreciated only with a magnifying lens. It is precisely the “sign” that we also find in his studies of anatomy or mechanics or hydraulics and is an essential tool of his method of investigation and of his going in deepness in the physical reality. The reason why the mountains of Leonardo appear so real is that he is the first painter who has studied their morphology and geological nature in depth, just as it would be impossible to effectively and realistically portray a human body without knowing the human anatomy.

This encounter between art and nature is the testimony of the beginning of the relationship between the Alps and Western culture which, as Philippe Joutard has amply illustrated (11), has its roots in the figurative creativity of the Renaissance, to gradually reaching maturity with the contribution of artists, humanists, historians and naturalists of the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries until the age of the Enlightenment, crowned by the conquest of Mont Blanc.

THE THREE drawings that we will consider are now in Windsor Royal Collections and catalogued as RL 12410 (10.5×16 cm), RL 12414 (15.9×24 cm) and RL 12411-12413 (5.4×18.2 cm, 7.2×14.7 cm). Published innumerable times both in books on the works of Leonardo (12), in studies on the relationship between Leonardo and the Alps and in various monographs on Monte Rosa, Mont Blanc or on the Alpine Panoramas (13), they are therefore well known also to whom is interested in alpine culture and alpinism history. But despite the fact that for some time there had been a direction towards a correct identification of the subjects (14), the snowy peaks of Monte Rosa have recently returned to be seen in them. (15) In these notes I would therefore like to give a safe, reasoned and definitive interpretation of these drawings, providing them with a detailed and certain description of the subjects and an identification of the point of recovery.

At the base of the positive results of this research there is simply the knowledge and the long familiarity with the profile of the Alps from Milan and with the landscapes of the Grigne and the Lombard Prealps. When the book by Virgilio Ricci on Leonardo’s alpine experiences appeared and I saw those drawings for the first time, I immediately recognized the real subjects, as if they were the faces of known people. For a historian or art critic who was not familiar with the profiles of the Alps it would have been difficult to arrive at the exact conclusion.

The sheet cataloged RL 12410 is the best known, because it is studied and published more frequently, certainly for its more accurate execution. In it we can distinguish three subjects: (a) a wide panorama that extends in the central part, (b) a small sketch in the lower central part and (c) a less extensive panorama in the upper right part. Almost always they have been referred to as “high snow-covered alpine peaks” sometimes “emerging from a sea of clouds” and referred to Monviso or, above all, to Monte Rosa (16); certainly due to the influence of the annotations on the Code Leicester related to the “mon Boso”, an ancient name of Monte Rosa. Only Carlo Pedretti rightly disagrees: “yet in the central drawing we can see a hint of the plain below: so it is not about peaks above banks of clouds, but of the same type of mountain represented in RL 12414”, i.e. mountains “of the landscape around Lake Como, north of Lecco “(17). And that’s right, but definitively the surprising point of observation was not suspected. They were in fact all executed from a site located in the center of Milan from which Leonardo could observe throughout the day. Perhaps he looked at the mountains from a tower of the Castello Sforzesco, or – even better- from the roof of the Duomo cathedral, a place he certainly visited for his documented tiburio project. This same place later on became famous as the best spot to observe the panorama of the Alps. In the Tour described by the Baedeker of the nineteenth century it was considered an obligatory stop (18).

The three subjects that Leonardo drew represent: (a) a view of the Lecco Prealps from Cornizzolo (left) to Pizzo dei Tre Signori (on the right) with the two twin pyramids of the Grigne in the middle; (b) a detail of the central sector of (a); (c) the Pizzo Arera in the Bergamo Prealps. Precision and detail are astonishing, Leonardo almost sixty years old had to be well-endowed with a very acute eyesight. In (a) many peaks are recognized; the most evident, from the left: the Cornizzolo, with the well identified and delineated valleys of the southern slope; the Monte Croce; with less clarity the Corni di Canzo; then the emerging top pyramid of Legnone with the south-east slope illuminated by the morning sun – well evident in (a) the light coming from the right (East)- then the summit of Grignone, note the smooth south-east side; then the Grignetta with the Torrioni Magnaghi in the middle of the ridge; then Pizzo Rotondo and Monte Melaccio; at the bottom, rising from the plain and highlighted in the foreground, Mount Due Mani; just a little above are the incredible two views of Pizzo Varrone and finally Pizzo dei Tre Signori. In (b) Leonardo redesigned the upper part of the panorama that goes from Legnone to Grignone, so the “marvel” of “peaks emerging from a sea of clouds” should be excluded (19). Then observing the illuminated slopes – light coming from the left (West)- it can be deduced that it was painted in the late afternoon, when the grazing light of the sun highlighted the details. The Sasso dei Carbonari and the Sasso Cavallo stand out (20); Leonardo saw these rocks closely, as he wrote in the Atlantic Code (21), when he visited the Ferrera cave above Mandello del Lario in val Meria (22), nestled at their base. In (c) the only Pizzo Arera is clearly defined, with just a hint of the Cima di Menna on the left. Why did he choose this mountain, certainly not much more high than others, and definitely much less notable than Monte Rosa, when this panorama is visible from Milan? Perhaps the reason is that, as for the walls of the Grigne, its forms were well known to him, rather familiar. In fact, in the frequent trips to Vaprio he could observe it just in front of him, as, in relation to Milan, it’s in the direction of Vaprio. Just as nowadays Pizzo Arera, on clear days, becomes the almost surreal background of Via Padova and should be familiar to non-inattentive of this permanently congested street. To this day, one can drive along it to join the main Padana Superiore road leading to Vaprio.

Another observation concerns the highlighting of white lead on some slopes and on the ridges. Probably it must have snowed on the mountains and therefore it was probably during winter or spring. This is possible, as these are the best times to observe the Alps from Milan: during these seasons when the sky is clear and the air is limpid, moreover with more oblique lights and a sprinkling of snow the details are highlighted even more. A detail that could be missed out could be noted observing some excellent and enlarged reproductions too. In the central panorama, at the extreme left of the sheet emerging from the western crest of Cornizzolo, sketched with a very light sign, a high triangular shaped mountain is visible: it corresponds precisely to Pizzo Stella, the beautiful peak north of Chiavenna. Being on the main watershed of the Alps it is more difficult to see, because when the favorable meteorological conditions – wind from the north – occur, the mountains of the watershed are often covered by clouds.

Finally, a hypothesis on the shooting technique suggested both by extreme precision in detail and by the observation that in the drawing the high elevations are more slender than in reality. By superimposing the drawing on a photo, one can see the perfect collimation – to the millimeter – of the position of the peaks and, on the other hand, the evident accentuation of the vertical scale in the drawing. This suggests the use by Leonardo of a shooting technique described in the aforementioned chapters of the Book of Painting or even of the perspectograph drawn in the Atlantic Code (23), with the peculiarity that the glass on which the image to be observed wasn’t vertical, but slightly inclined, with the consequence of lengthening the vertical dimension.

Another Alpine panorama outlined by Leonardo is the one on sheet RL 12414. In reality, there are two of them on the sheet, of which the upper one is a little more than outlined and the lower one is more complete. The less care which is noticeable when compared to RL 12410 makes us think of sketches taken during a trip. A confirmation of this is also provides by the subject on the sheet made up of the two fragments RL 12411 and 12413. These drawings could in fact illustrate a sort of “picturesque journey along the west bank of the river Adda”, having portrayed the Prealps of Lecco taken from sites very closed to the Milanese bank of the Adda.

Who knows, perhaps Leonardo was carrying out inspections for his hydraulic studies of the Paderno Canal, of which he had planned the famous sluice, or was merely making a simple excursion. On the sheet RL 12414, the main subject is the panorama of the Prealpi of Lecco in the stretch that goes from the Grigne (left) to the Albenza (right) and was taken on the western edge of the deep Adda canyon in a locality about 2 km upstream of Trezzo, and therefore only 6 km from the villa Melzi of Vaprio, in which Leonardo was long hosted. Proceeding from the right we recognize the long coastline of the Albenza with a fine definition of the various ridges that descend to the south-west; then the Monte Tesoro precedes the rugged profile of the Resegone, which from here appears remarkably by its profile and then, beyond the crack of Valsassina, there is the smooth south-east slope of Grignone and the rugged Grignetta with its spires and finally to left against the sky there is the west ridge. Called “Cresta Segantini” and very popular with Lombard mountaineers, it is faithfully outlined with the adjacent fortified towers, among which certainly stands the mighty Cecilia Tower. The long ridge with patches of trees that extends along the entire length of the sheet, covering the bases of the mountains mentioned above, and which has its summit corresponding to the Resegone, is Monte Canto, to which southern base is located Sotto il Monte John XXIII, and to the north Pontida, place of the historical oath. This hill, which lies a few kilometers further south of the main chain, allows us to identify the exact observation point of Leonardo, which is where its summit is positioned under the summit of Resegone. In this case too, the real panorama is somewhat more “flat”. Indeed here the difference is much more marked making the correspondence between drawing and photo not so evident at first glance. manca un pezzo di traduzione. But even though Leonardo has used a larger sheet he has accentuate the vertical scale and narrow the horizontal one more clearly than in RL 12410. Due to the remarkable wildness of the place even today it is difficult to find a hole in the thick vegetation to observe the view.

A series of sketches is observed in the upper right part of the paper. A top with slender shapes on the left could be M. Barro seen from SSO. There are some hills, one of which is surmounted by a tower that could be the hill of Montevecchia or the Brianza hill with the famous Campanone(towerbigbell), the ancient tower of Teodolinda still intact to this day. But they would not be compatible with the higher mountains in the background. These are again to be identified with the Grigne: they are in fact recognizable by the rough lines of Grignetta, above which emerges the more regular crest of Grignone and, more to the right it is possible to identify the profiles of Resegone and Monte Tesoro, all taken from a position not very different from that of the main view. The pre-Alpine aspect of these views, highlighted by long wavy ridges, had been identified by almost all commentators (24), with the exception ascribed to the usual Monte Rosa portrayed from Alpe Bors in Val Sesia (25).

The text written in the lower margin of the sheet refers to the color and the azure atmosphere that surrounds the mountains, especially in their shaded areas and the influence of vegetation and stones in the color of the mountains. Recently deciphered by the help of infrared photography, it is in tune with similar texts of the Book of Painting (26). Finally note that, compared to the times of Leonardo something, unfortunately worse, has changed: now the Albenza, as well as the Cornizzolo, on top of being disfigured by numerous antennas are devastated by colossal caves that feed the nearby cement factories. So the little hole that Leonardo had made to extract some fossils, and which created turmoil among the suspicious inhabitants of the place (27), has become an immense chasm in perpetual growth.

The third view, the one drawn on the sheet composed of the two catalogued fragments RL 12411 and 12413, is the only one that has so far been identified. In fact, as Carlo Pedretti states, “it represents a scabrous profile, characteristic of the mountains above Lecco, that is the well-known Resegone, which is probably recognized in the reconstructed drawing […]”(28). Indeed, precisely the mountain subject of the famous lapsus of the poet G. Carducci! In an even more evident lapse there is a denial of this correct identification, attributing it to the region of the usual Monte Rosa (29), but refraining from specifying the subject and the point of observation. This is instead exactly identifiable on the Rocchetta near Airuno, a characteristic panoramic summit overlooking the wide meander of the Adda, of which the winding course flanked by trees can be seen in the lower part of the drawing. Already outpost of the Venetian Republic, this strategic hill was annexed to the Duchy of Milan in 1450. Now there is a picturesque Sanctuary and from its beautiful portico there is a wide view of the Adda valley and the Prealps from the Grigne, Resegone and Albenza.

MANY OTHER drawings of Leonardo have for subject mountains, mostly rocky. However, I think we should consider them preparatory studies for the backgrounds of his important pictorial works and not life taken. Even the dramatic alpine landscape with storm in RL 12409, where an urban conglomeration is located in a basin enclosed by high rocky mountains, is certainly a landscape produced from imagination, even if inspired by the many real experiences made in alpine and pre-alpine environments. In it the shape and disposition of the mountains have a “step” and a “scale” that respond more to free creation and that we find similar in RL 12405 and also in the background of the Virgin and S. Anna painting. A simple comparison with the three sheets that have been analyzed here is enough to convince oneself that only these are certainly studies from real life: in them the “sign” is clear, essential and analytical, in others it is blurred, more aimed at creative rather than documentary needs.

Therefore, the true “portraits” of the Leonardo’s Alps are the Lombard Prealps. The relative closeness of these mountains to its residences of Milan and Vaprio, having walked the slopes, visited the contiguous valleys, the woods, the mines and the natural curiosities has surely left in its soul a sweet feeling of familiarity. A feeling that is renewed in all those who love the mountains when they see them from far away. In 1511 Leonardo, turning towards old age, seeing them from Milan on a clear sunny day, or during a trip along the Adda has fixed the memory of distant experiences, perhaps even adventures, on those sheets of “sanguigna” that, by their size , they have been nicely defined souvenir-postcards (30).A certain regret catches us if we think instead of the lack, at least so far, of graphic testimonies of the so mysterious and fascinating ascent to the “mon Boso”. The attempt to associate the Red Serie drawings with this ascension has therefore proved futile. If the Monte Rosa gallery of portraits is lacking of important pieces of Author of our Alpine giant, it is not so important as its grandeur and charm are already great and will remain so. But on the other hand, the poor, modest, tortured and violated Cornizzolo and Albenza will have at least a little thrill of pride.

(Published in “Achademia Leonardi Vinci, Journal of Leonardo Studies & Bibliography of Vinciana”, Vol X, 1997, pp. 125-133, 8 pp. of plates)

NOTES

1 Gerolamo Calvi, Life of Leonardo, Brescia, 1936, p. 58. Posthumous publication reviewed by Enrico Carusi in “Raccolta Vinciana”, XV-XVI, 1935-1939, pp. 321-23.

2 Interest in the Alps in Italy remained, after Leonardo, long dormant. To the north of the Alps, on the other hand, it remained alive, even in a narrow circle of historians and humanists (Aegidius Tschudi, De prisca ac vera Alpina Rhaetia, Basel, 1538, Josias Simler, Vallesiae Descriptio – De Alpibus Commentarius, Zurich, 1574, Ulrich Campell , Rhaetia Alpestris topographica descriptio), in whose texts, primary in the sixteenth century, are not only data drawn from classical sources, but also news and information from direct experiences or contemporaries. This does not happen in our Flavio Biondo (Italia Illustrata, 1451), or Leandro Alberti (Descrittione di tutta l’Italia …, Bologna, 1550), or Gaudenzio Merula (Gallorum Cisalpinorum antiquitate ac origine, Bergamo, 1592). Even in the figurative arts the Alps are a subject especially for artists from the Nordic area, such as Dürer, Altdorfer, Pieter Bruegel. One exception is Titian who, born in the heart of the Dolomites of Cadore, sometimes seems to remember the landscapes of his childhood, like in the background of the Presentation of the Virgin at the temple. It is with the eighteenth century that interest begins to grow, starting with J. J. Scheuchzer, Itinera Alpina …, London, 1708 (2nd ed., Leiden, 1723), Albrecht von Haller, Die Alpen, Berne, 1732, a poem which, translated into various languages (Italian in 1768, Yvérdon), was widely diffused and constituted a decisive element for the definitive ‘discovery’ of the Alpine world, as well as the epistolary novel by J. J. Rousseau, La Nouvelle Héloïse, 1761. the scientific-geographical works of J. G. Altmann and G. S. Gruner on Alpine glaciers, the Deluc brothers, M.T. Bourrit and especially H. B. de Saussure, the promoter of the first ascent of Mont Blanc (by Gabriel Paccard and Jacques Balmat in 1786) and author of the Voyages dans les Alpes, 4 vols, Neuchâtel, Geneva, 1779-96, which definitively opens the doors of the Alps to universal knowledge. To the south of the Alps are mainly botanists and naturalists who shyly enter the alpine valleys. But in order to find a figurative testimony that, after Leonardo, significantly affects the Alps we must wait for the mid-eighteenth century (1744) with the painting by Bernardo Bellotto, View of Gazzada and the Villa Melzi d’Eril, which has in the background the Alpine chain and the Monte Rosa. It is enough, however, to observe the difference between the precision of detail in the foreground and the botched definition of the Alpine chain to perceive the inadequacy of the reading and the understanding of the Alpine landscape that was then. From the second half of the eighteenth century,even in Italy began a more widespread interest. this is witnessed by the explorations of some intrepid youngster from Gressoney in 1778, 1779 and 1780, at the extremity of their valley, still wrapped in an almost legendary aura. The astronomers Padre Beccaria and later Barnaba Oriani in 1788, on the occasion of geodesic triangulations from Turin and Milan, measured the height of Monte Rosa. De Saussure magnifies the view of the Alps from Turin and Vercelli and visits the southern valleys of Monte Rosa in 1789, just preceded, in 1785 in Macugnaga, by Carlo Lodovico Morozzo della Rocca. Nicolis di Robilant published, in 1790, the results of his travels in the mineral areas of Piedmont with extensive descriptions and numerous views. The first ascent is by doctor Pietro Giordani of Alagna Valsesia, in 1801, to a high peak of Monte Rosa. The careful study of Ludwig von Welden, Der Monte Rosa, Vienna, 1824 (translation with an introduction edited by the Monti Foundation, Anzola d’Ossola 1987), summarizes and concludes, with a work that is important alongside that of De Saussure, the phase of the pioneers opening from the south the streets of the Alps not only to naturalists and scholars, but also to tourists and mountaineers. Von Welden, long resident in Milan following the Austrian army and protagonist in the first Risorgimento events, was fascinated by the vision of the Alps from the Po Valley and in particular by the imposing and elegant lines of Monte Rosa.

3 CA, f. 214 r-e, c. 1490-2 (Richter, § 1030).

4 Ibid. An illustration of this document is in Mario Cermenati, Leonardo in Valsassina, Milan, 1910.

5 Codex Leicester, Charter 4A, f. 4 r.